Anonymous Votes with Nothing but Math

How I built a trustless voting system where no one — not even the organizer — can see your ballot, using a 1988 cryptography trick and wallet signatures.

We used to pick employee of the month with a Google Form. It started as single-choice — pick one person — but we kept getting ties at the top. Turns out when your whole team is productive, everyone gets votes. So we switched to ranked choice with point weights (5 for 1st, 3 for 2nd, 1 for 3rd) and built a simple voting app with a central database to handle it.

Worked great. Nobody really cared that the organizer could technically see individual votes — we're a chill team. But I work at a crypto company, and the idea of a voting system backed by a trusted central server felt like it deserved a better answer.

Try it live: ballot-zero.vercel.app · Source code: github.com/Royal-lobster/BallotZero

The Problem

I wanted a voting system with a specific set of constraints:

- No backend. The entire thing runs in the browser. I don't do backends for side projects.

- Wallet-based identity. Everyone at the company already has an Ethereum wallet. No new accounts.

- Ranked choice with configurable weights. We need [5, 3, 1] point allocation to break the ties that single-choice kept producing.

- Ballot privacy. When a voter submits, their output should reveal nothing about their actual vote. Not to the organizer, not to other voters, not to anyone.

- Verifiable tally. Anyone should be able to independently confirm the result is correct — no "trust me, I counted right."

- No time limits, no coordination server. The organizer manually collects ballots and aggregates when ready. Communication happens over whatever channel the team already uses — Slack, Signal, links in a group chat.

The tricky part is doing ballot privacy and verifiable tallying without a server. Usually you need a trusted party somewhere — to hold a decryption key, to shuffle ballots, to coordinate a multi-party computation. I wanted to see if I could get rid of that entirely.

Picking an Approach

Three approaches kept coming up when I researched anonymous voting:

| Approach | Privacy | Verifiable | Trade-off |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homomorphic encryption | Votes encrypted, tally computed on ciphertext | Anyone can verify the encrypted sum | A key holder exists — someone can decrypt individual votes |

| Threshold decryption | Votes hidden until k-of-n parties cooperate to decrypt | Strong, auditable | Complex setup, multiple parties must coordinate key shares |

| DC-net (pairwise masking) | Information-theoretic — unbreakable unless all other voters collude | Anyone can re-sum the published ballots | Fragile — every voter must participate or the tally breaks |

Homomorphic encryption is the industry standard, but it always has a key holder — and whoever holds the private key can decrypt any individual ballot. You can restrict the UI, but you can't restrict algebra. Threshold schemes distribute that trust across multiple parties, but the coordination overhead is brutal for a fun office vote. DC-nets trade robustness for something I cared about more: zero trust assumptions. No keys to hold. No parties to coordinate. No one can cheat, not just "won't."

For 10 coworkers who all show up anyway? The fragility is a non-issue. I picked DC-nets.

A cryptographer named David Chaum invented them in 1988. He just wasn't thinking about employee-of-the-month votes.

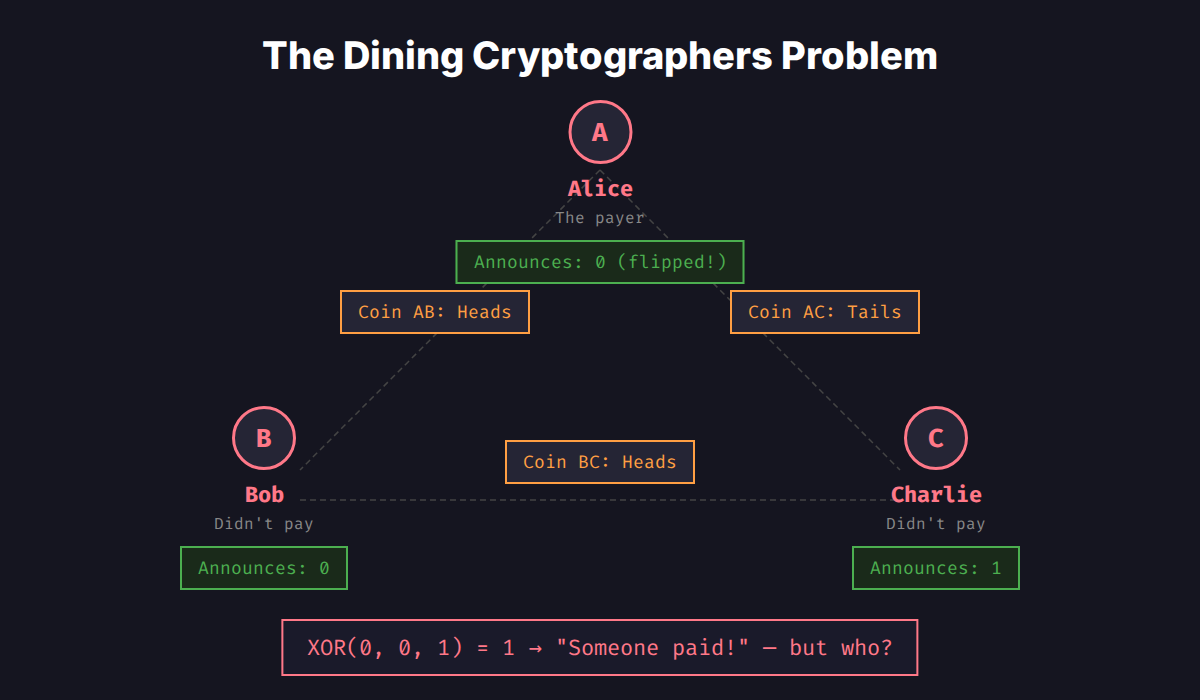

The Dining Cryptographers Problem

Three cryptographers sit down for dinner. The waiter tells them the bill has already been paid — either by one of them, or by the NSA. They want to know which: did one of them pay, or did the NSA? But if one of them did pay, they don't want the other two to know which one.

Here's Chaum's trick. Each adjacent pair of cryptographers secretly flips a coin under the table. So with three people, there are three shared coins — one between each pair. Each cryptographer sees exactly two coins: the ones they share with their neighbors.

Then each cryptographer announces a single bit:

- If they didn't pay: announce whether their two coins match (same = 0, different = 1)

- If they did pay: announce the opposite — flip their answer

The punchline: XOR all three announcements. If the result is 0, the NSA paid. If it's 1, one of the cryptographers paid. But you can't tell which cryptographer flipped their answer — the shared coins act as masks that cancel out when combined.

That's a DC-net. Dining Cryptographers Network. And it generalizes beautifully. Chaum's protocol sends one anonymous bit. I need to send an anonymous vote vector — one number per candidate. The core idea stays the same, but instead of coin flips I use elliptic curve Diffie-Hellman to generate shared secrets between wallet-derived keypairs.

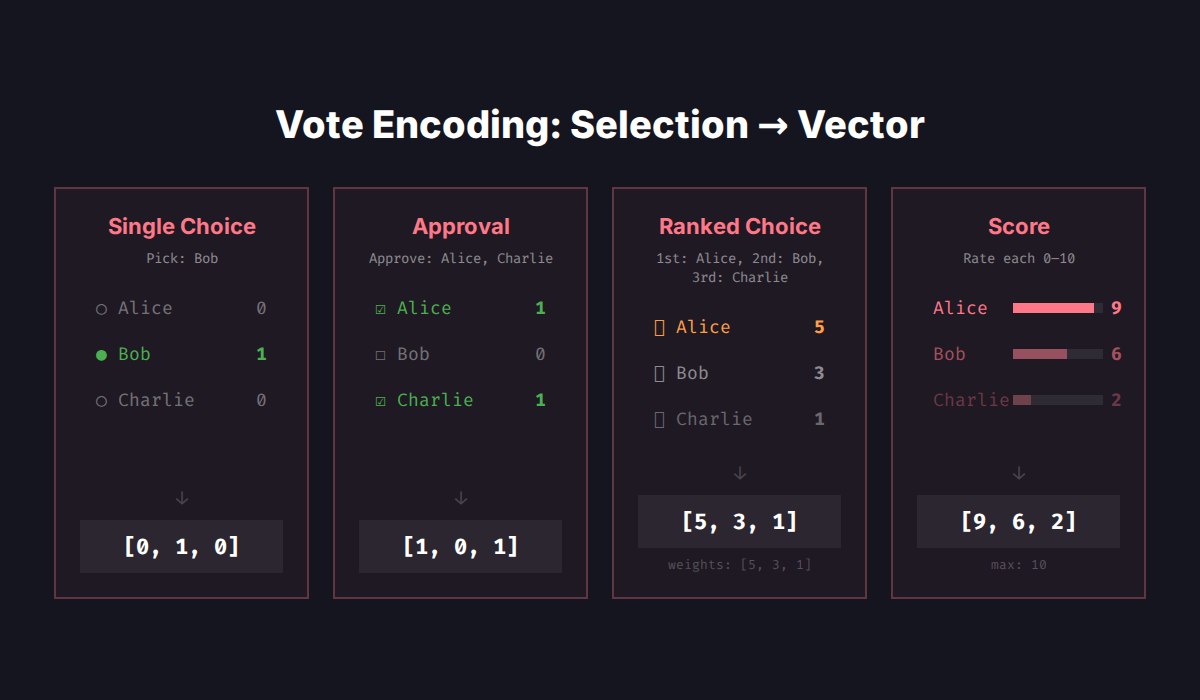

Encoding Votes

Before masking anything, I need to define what a "vote" looks like as data. BallotZero supports four voting methods. Each produces a vote vector — an array of integers, one per candidate:

Single choice: Pick one candidate. Their slot gets 1, everything else gets 0. Three candidates, you pick the second one: [0, 1, 0].

Approval voting: Pick as many as you like. Each approved candidate gets 1. Approve candidates 1 and 3: [1, 0, 1].

Ranked choice: Rank candidates in order. The position maps to configurable point weights — by default [5, 3, 1] for 1st, 2nd, 3rd place. If you rank Alice 1st, Bob 2nd, Charlie 3rd with weights [5, 3, 1], your vote vector is [5, 3, 1]. The weights are part of the election config, so they're agreed on before anyone votes. Want a Borda count? Set weights to [3, 2, 1]. Want to heavily favor first place? [10, 3, 1].

Score voting: Rate every candidate on a scale — say 0 to 10. Give Alice a 9, Bob a 6, Charlie a 2, and your vote vector is [9, 6, 2]. Unlike ranked choice, you can express how much you prefer one over another.

The protocol doesn't care which method you pick — it just sums vectors.

Now the question: how do you publish these vectors without revealing who voted for what?

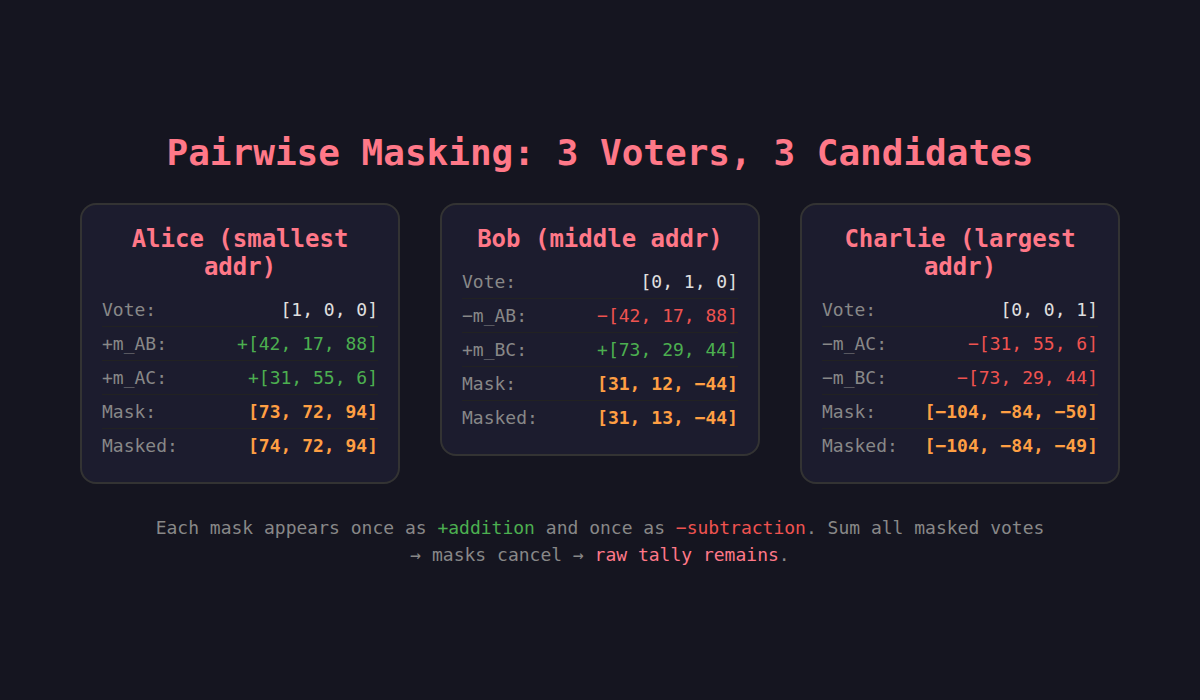

The Pairwise Masking Protocol

Say three voters — Alice, Bob, and Charlie — are voting in an election with 3 candidates. Each pair generates a shared secret using ECDH on secp256k1:

- Alice ↔ Bob: Alice's secret key × Bob's public key = Bob's secret key × Alice's public key. Same point on the curve. Math is beautiful like that.

- Alice ↔ Charlie: Same idea, different shared point.

- Bob ↔ Charlie: Same idea, yet another shared point.

From each shared secret, I derive a mask vector — one mask value per candidate slot — using SHA-256. The derivation is deterministic: SHA-256(shared_x || shared_y || election_id || component_index), reduced modulo the curve order.

The direction matters. For each pair, I sort by Ethereum address. The voter with the smaller address adds the mask. The voter with the larger address subtracts it. This is what makes everything cancel:

For any pair (i, j) where address_i < address_j:

- Voter i's mask includes +mask_ij

- Voter j's mask includes −mask_ij

Sum them? Zero. Every mask appears once as addition and once as subtraction. Gone.

The Math That Makes It Work

Time for a concrete example. Three voters, three candidates, single-choice voting. All arithmetic mod the curve order n — but I'll use small numbers to keep things readable.

Say:

- Alice votes for Candidate A → vote =

[1, 0, 0] - Bob votes for Candidate B → vote =

[0, 1, 0] - Charlie votes for Candidate C → vote =

[0, 0, 1]

Three ECDH pairs produce three mask vectors (one value per candidate slot). Let's call them:

- m_AB =

[42, 17, 88]— the mask between Alice and Bob - m_AC =

[31, 55, 6]— the mask between Alice and Charlie - m_BC =

[73, 29, 44]— the mask between Bob and Charlie

Address order determines sign. Assume Alice < Bob < Charlie:

| Voter | Vote | Mask computation | Total mask |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alice | [1, 0, 0] | +m_AB + m_AC | [73, 72, 94] |

| Bob | [0, 1, 0] | −m_AB + m_BC | [31, 12, −44] |

| Charlie | [0, 0, 1] | −m_AC − m_BC | [−104, −84, −50] |

Each voter adds their mask to their vote: masked_vote = vote + mask (mod n).

| Voter | Masked vote |

|---|---|

| Alice | [74, 72, 94] |

| Bob | [31, 13, −44] |

| Charlie | [−104, −84, −49] |

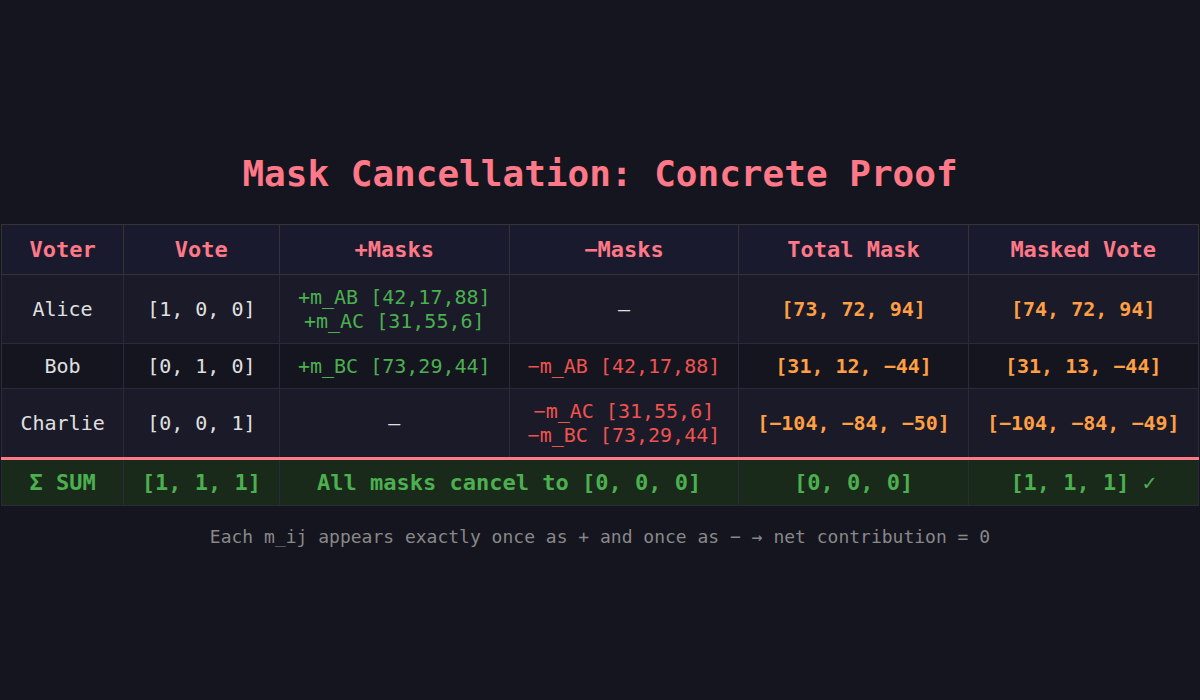

Sum all masked votes:

[74 + 31 + (−104), 72 + 13 + (−84), 94 + (−44) + (−49)]

= [1, 1, 1]The masks vanish. What's left is the raw tally: Candidate A got 1 vote, Candidate B got 1, Candidate C got 1. Nobody knows who voted for what — they only see the masked vectors, which look like random noise.

In the real implementation, all values are 256-bit integers modulo the secp256k1 curve order. You can't reverse-engineer the mask from the masked vote because you'd need to know the ECDH shared secret, which requires knowing someone's private key.

Key Derivation from Wallets

Voters already have Ethereum wallets. I don't want them managing another keypair. So BallotZero derives one from a wallet signature.

During onboarding, the voter signs a fixed message: "BallotZero:onboard". The app takes that signature, hashes it with SHA-256, and uses the result as a secp256k1 private scalar. Multiply by the generator point, and you've got a public key.

signature = wallet.sign("BallotZero:onboard")

esk = SHA-256(signature) mod (n - 2) + 1

epk = esk × GThe wallet signature acts as a high-entropy seed — deterministic, so the same wallet always produces the same BallotZero keypair. It's separate from the wallet's actual keys, so there's no risk of leaking the wallet's private key. The mod (n - 2) + 1 clamps the result to a valid scalar in [1, n-1].

When casting a vote, the voter signs a different message — a hash of their election ID and masked vote vector — so there's no signature reuse between onboarding and voting.

Security Properties

What BallotZero guarantees:

- Ballot secrecy — no single party can determine any voter's choice. You'd need to collude with all other voters to unmask a single ballot.

- Integrity — each masked vote is signed by the voter's wallet. You can't forge or tamper with ballots.

- Verifiability — anyone can verify the aggregation by summing the masked vectors themselves.

- No trusted party — no server holds decryption keys. The math does the work.

What it doesn't guarantee:

- Availability — here's the trade-off. Every registered voter must submit a ballot for the tally to work. If Alice doesn't vote, her mask component doesn't cancel, and the sum is garbage. This is fundamental to the DC-net design — you can't have both "masks cancel perfectly" and "some masks are optional." I could add dummy votes or threshold schemes, but that adds complexity and trust assumptions I wanted to avoid.

- Disruption — a malicious voter could submit a malformed mask and silently corrupt the tally. Classic DC-net weakness. BallotZero mitigates this with wallet signatures on every ballot, but it doesn't fully prevent a voter from intentionally poisoning their own mask computation.

- Coercion resistance — a voter could prove how they voted by revealing their private key. BallotZero doesn't have receipt-freeness.

- Traffic analysis resistance — the app doesn't try to hide when you vote or that you vote. Just what you vote.

For an employee-of-the-month vote among 10 people who all know each other? These trade-offs are fine. For a national election? You'd want more machinery.

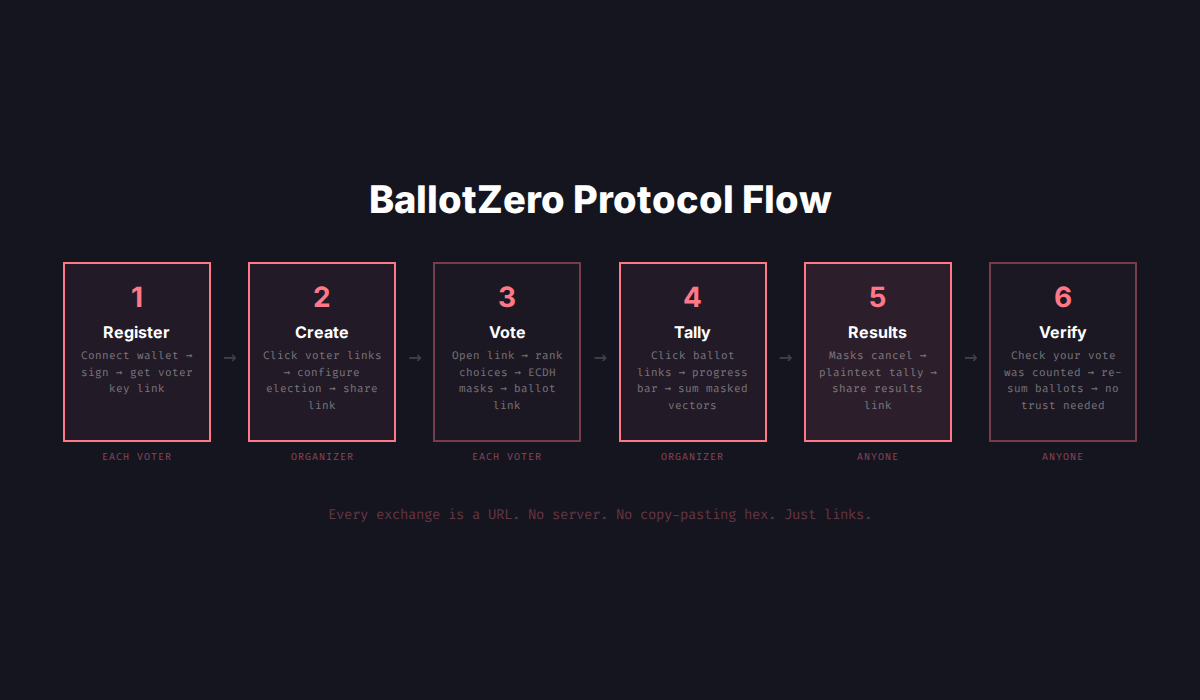

The Flow

No backend. The tricky part: with no server, how do participants exchange data? The answer is URLs. Everything is a link.

1. Register — Each voter visits /join, connects their wallet, and signs "BallotZero:onboard". The app derives their BallotZero keypair and generates a voter key link — a URL containing their address and compressed public key as base64. They share this link with the organizer.

2. Create — The organizer visits /create. When a voter shares their key link, the organizer just clicks it — the app reads the URL parameters and automatically adds the voter to IndexedDB. No copy-pasting hex strings. Once all voters are added, the organizer configures the election (title, candidates, voting method, point weights) and generates a shareable election link.

3. Share — The organizer sends each voter their voting link.

4. Vote — Each voter opens the link, connects their wallet, and makes their choice. The app locally computes their mask vector (ECDH with every other voter), adds it to their vote vector, and produces a masked ballot. The voter gets a ballot link — another URL encoding their masked ballot — to share back with the organizer.

5. Tally — The organizer opens /tally. Same trick — when voters share their ballot links, the organizer clicks each one, and the ballot is automatically added to the tally page. A progress bar shows how many ballots have been collected out of the total. Once everyone's in, the app sums the masked vote vectors modulo the curve order.

6. Results — The masks cancel. The sum is the plaintext tally. The organizer shares a results link with everyone.

7. Verify — Anyone can verify that their vote was included and that the final tally matches the submitted ballots. No trust required.

The entire flow is URLs and clicks. No copy-pasting cryptographic blobs, no server coordinating state. IndexedDB stores everything locally — the organizer's browser is the "backend." Share links over Slack, Signal, email, whatever you trust. BallotZero doesn't care about the transport.

Try It

Run a vote at ballot-zero.vercel.app. Grab three friends with wallets, register everyone, create an election, vote, tally. Watch the masks disappear.

The full source — about 300 lines of actual crypto logic — is on GitHub. The interesting bits are in app/lib/crypto.ts.

References

- Chaum, "The Dining Cryptographers Problem" (1988) — the original paper

- DC-net on Wikipedia — accessible overview

- secp256k1 curve parameters — the elliptic curve BallotZero uses

- @noble/curves — the JS library doing the heavy lifting