How I Squeezed Drum Beats into URLs

Fitting an entire drum machine's state into a shareable URL with adaptive arithmetic coding — no database, no server, no accounts.

Ever tried sharing a URL that's longer than the content it links to? BeatURL lets you make drum patterns and share them — but the pattern lives in the URL itself. No database, no server, no accounts. Just a link.

Try it live: beaturl.vercel.app · Source code: github.com/Royal-lobster/beaturl

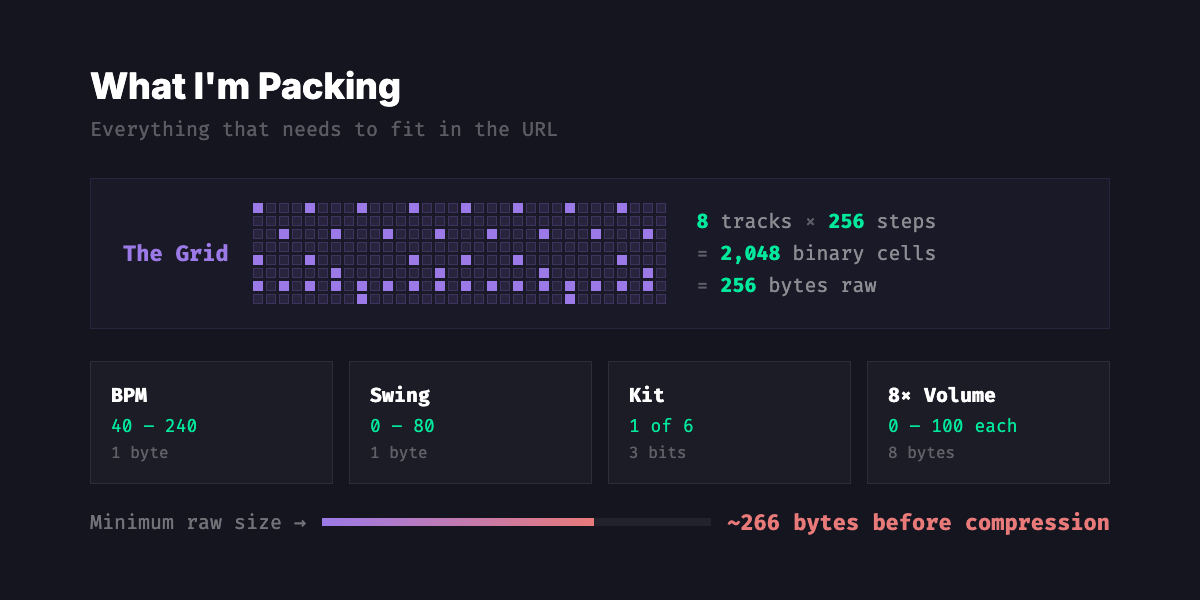

The catch? An 8-track, 256-step grid is 2,048 binary cells. That's 256 bytes before you even add BPM or volume info. Base64-encode that and you've got a URL longer than this paragraph.

So I went looking for a better way.

A Quick Detour Through 1948

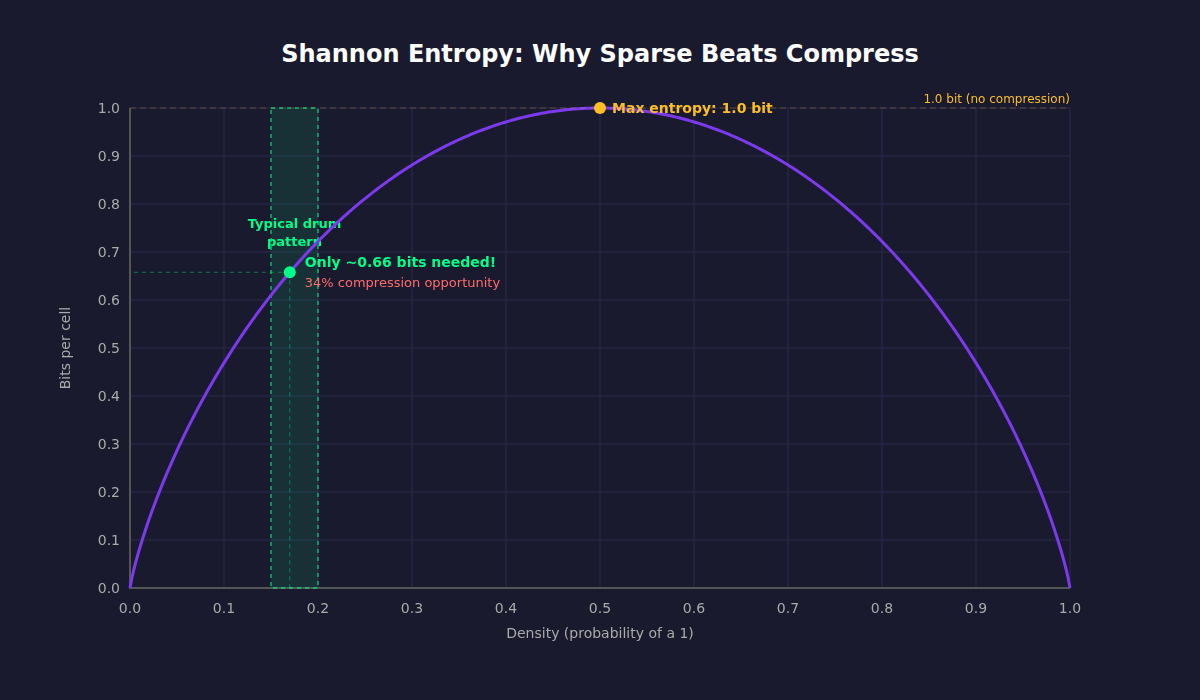

Before compressing anything, I need to know how much I can compress. Claude Shannon figured that out 78 years ago.

Shannon's key insight: the less predictable your data is, the more space it takes to describe it. He called this entropy — the theoretical minimum number of bits needed to encode a message.

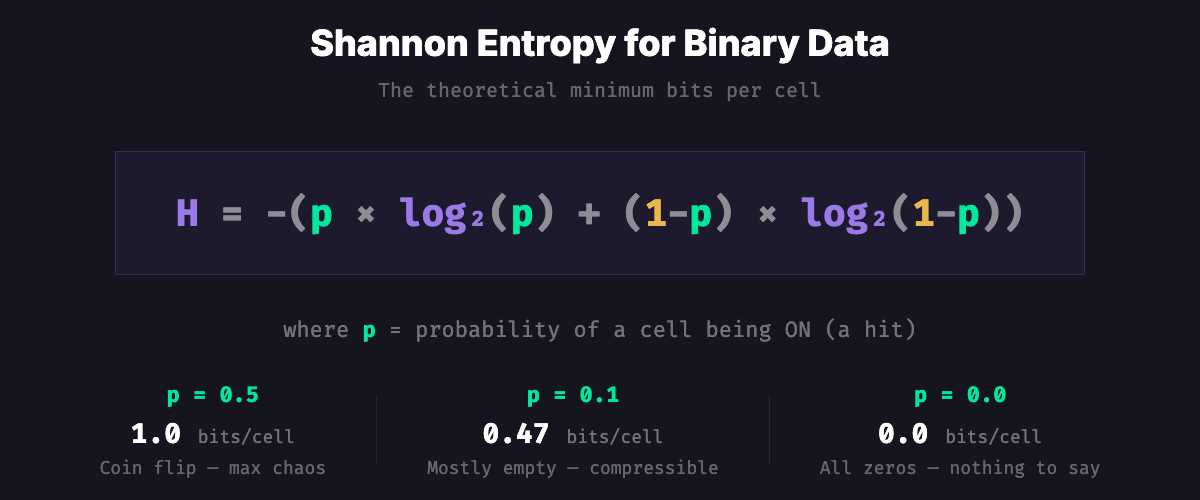

For binary data (just 0s and 1s), the formula is:

Most drum patterns are sparse. A typical beat might be 15–20% filled. Shannon says I should be able to represent each cell in far less than one bit. The question is how.

Entropy drops even further when bits are correlated. In a beat pattern, if this step is a kick, the next step almost certainly isn't. An encoder that notices these patterns can squeeze out even more.

Shannon proved this is a hard floor — no lossless compressor can ever beat the entropy rate. So I have a target to aim for.

What I'm Packing

My old encoding used hex digits per row with dot separators. A 236-step beat? 515 characters. Try fitting that in a tweet.

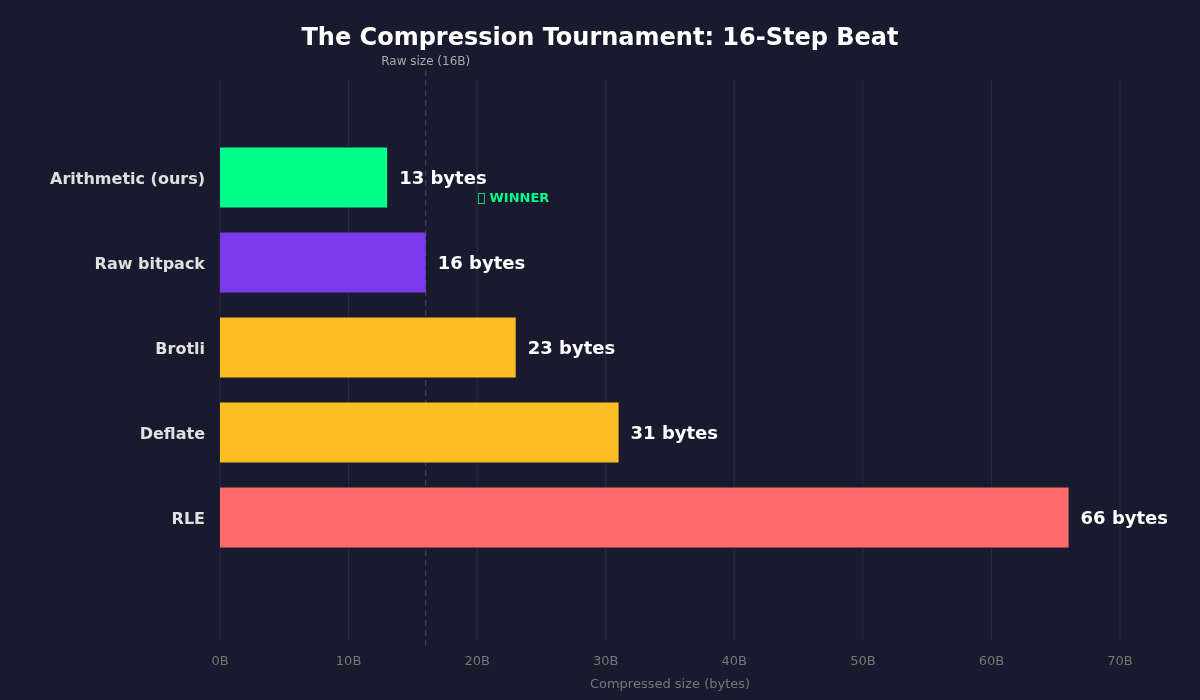

The Compression Tournament

I tried five approaches. Most of them lost.

Round 1: Raw Bitpacking

The simplest thing that could work: one bit per cell, eight cells per byte.

A 16-step grid becomes 16 bytes. A 256-step grid becomes 256 bytes. No intelligence, no savings. This is the baseline.

Verdict: Honest, but unambitious.

Round 2: Run-Length Encoding

RLE encodes streaks — "42 zeros, then 1 one, then 3 zeros..." Works great for fax machines and pixel art. Works terribly for drum beats.

Why? A kick pattern like 1000100010001000 has short alternating runs. Each run needs a value byte and a count byte. A 16-step beat ballooned to 66 bytes. That's 4× worse than raw bitpacking.

Verdict: Showed up to a knife fight with a spoon.

Round 3: Deflate and Brotli

The heavy hitters — the algorithms behind gzip, ZIP files, and HTTP compression. Surely they'd crush this little grid?

Nope. On a 16-step beat:

- Deflate: 31 bytes (nearly 2× worse than raw)

- Brotli: 23 bytes (still worse than raw)

The problem is overhead. These compressors ship a whole toolbox with every output — Huffman tables, dictionary headers, block markers. That toolbox weighs more than the actual data. They're built for compressing web pages, not 16-byte grids.

Verdict: Bringing a semi truck to deliver a letter.

Round 4: Arithmetic Coding

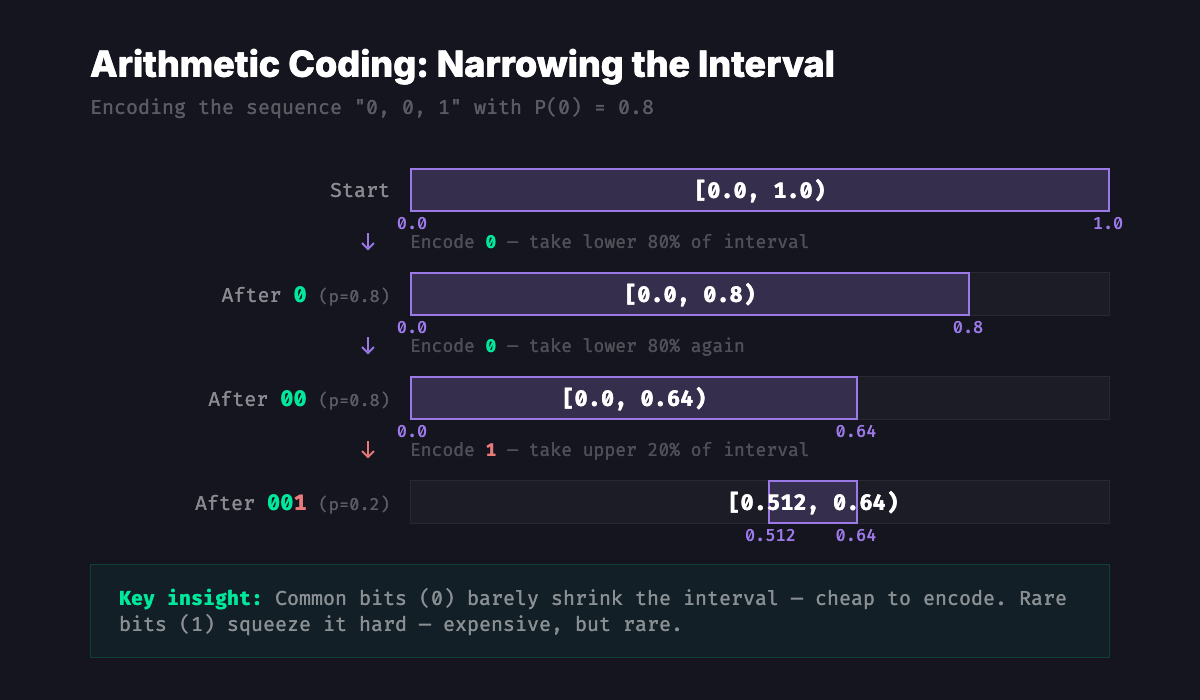

Instead of assigning fixed codes to symbols (like Huffman does), arithmetic coding represents the entire message as a single number between 0 and 1. Each bit narrows the interval:

More probable symbols barely move the interval — cheap. Rare symbols squeeze it hard — expensive, but rare. The final interval width tells you how many bits you need. Gets within 1–2 bits of Shannon's theoretical limit.

Verdict: Getting somewhere.

Round 5: Adaptive Arithmetic Coding

The winning approach. The encoder starts knowing nothing about the data — it assumes 50/50 for every bit. But as it encodes, it learns. After seeing a few bits of a sparse track, it figures out "oh, 0s are way more common" and starts encoding 0s cheaply.

The decoder does the exact same learning in the exact same order. No probability tables, no side information, no overhead. Just the raw bitstream.

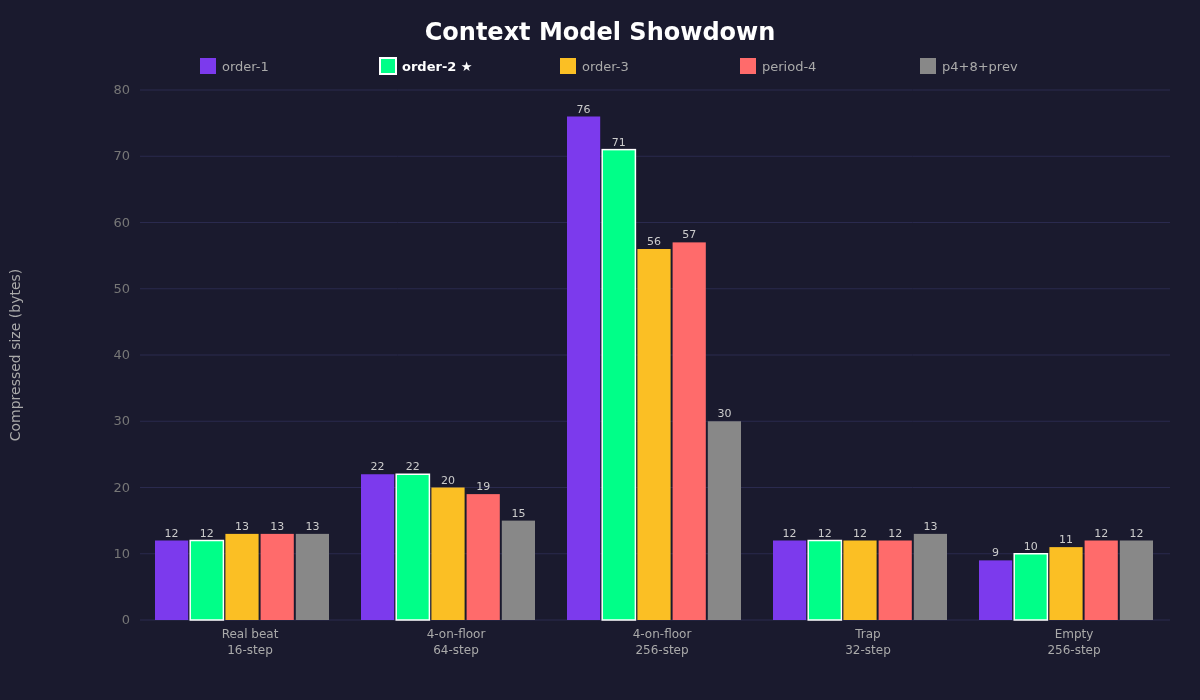

The Context Model Showdown

An arithmetic coder is only as good as its predictions. The context model decides what information to use when predicting the next bit. I tested five:

| Model | How it predicts | Contexts |

|---|---|---|

| Order-1 | Looks at the previous bit | 2 |

| Order-2 | Looks at the previous 2 bits | 4 + startup |

| Order-3 | Looks at the previous 3 bits | 8 + startup |

| Period-4 | Looks at the bit 4 steps ago | 2 |

| Period-4+8+prev | Looks at bits 4 and 8 steps ago + previous | 8 |

Period-aware models are musically clever — they know that beats tend to repeat every quarter note. But cleverness has a cost: more contexts means more to learn, and small grids don't have enough data for the model to warm up.

The Benchmark

Grid entropy in bytes (lower is better):

| Pattern | order-1 | order-2 | order-3 | period-4 | p4+8+prev | raw |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real beat 16-step | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 16 |

| 4-on-floor 16 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 16 |

| 4-on-floor 64 | 22 | 22 | 20 | 19 | 15 | 64 |

| 4-on-floor 256 | 76 | 71 | 56 | 57 | 30 | 256 |

| Breakbeat 16 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 16 |

| Trap 32 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 32 |

| Polyrhythm 128 | 81 | 70 | 60 | 73 | 56 | 128 |

| Empty 16 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 16 |

| Empty 256 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 256 |

| Pseudo-random 64 | 60 | 54 | 33 | 40 | 44 | 64 |

What the Numbers Say

Short grids (4–16 steps): Order-1 and order-2 tie or win. Fancier models have too many contexts and not enough data to fill them — the Laplace prior overhead eats any theoretical gain.

Medium grids (32–64 steps): Order-2 and order-3 do well. Period-4 starts helping on repetitive patterns but hurts on irregular ones.

Long repetitive grids (128–256 steps): Period-4+8+prev crushes it. A 256-step four-on-the-floor compresses to 30 bytes vs 71 for order-2. It knows the music.

Long non-repetitive grids: Order-3 edges ahead. On a 236-step hand-drawn beat, it saved 6 bytes over order-2. Five percent.

Why I Picked Order-2

- Wins where it matters — most beats are 16–32 steps

- Close enough everywhere else — within 5% of the best model on long grids

- Dead simple — four contexts, one code path, no branching on grid size

- Fast learner — with only 4 contexts to fill, it adapts in the first few bits

The maximum gain from always picking the perfect model? About 8 URL characters on a 236-step beat. Not worth the complexity. Shipping beats, not PhD theses.

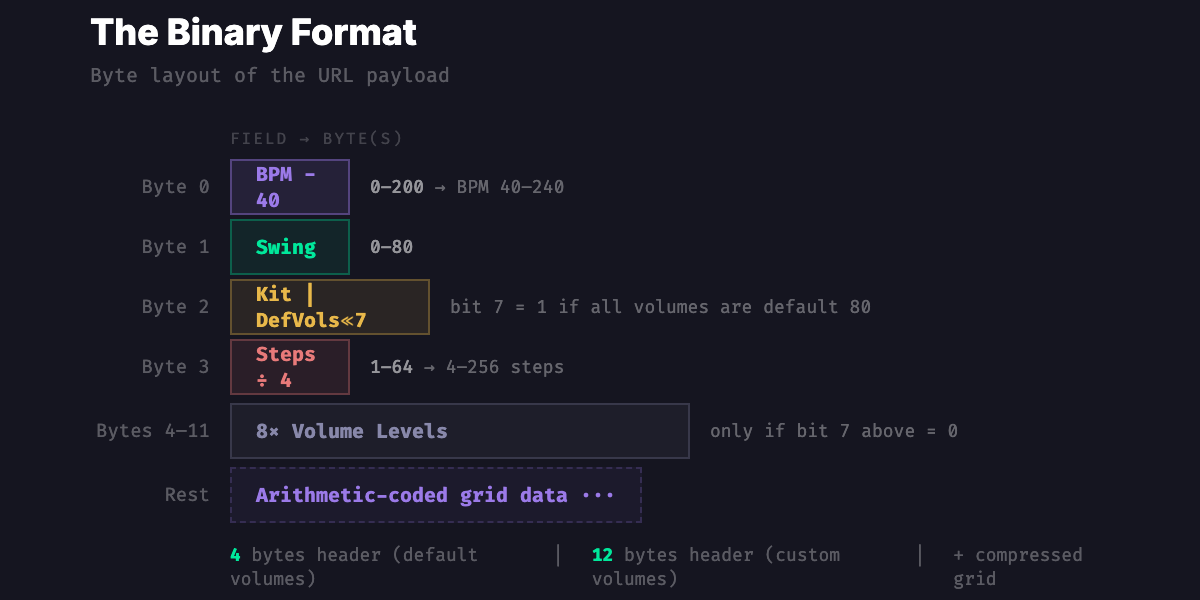

Under the Hood

The Binary Format

Four bytes of header when volumes are default. Twelve if you've tweaked them. Then the compressed grid.

The Range Coder

I use a 48-bit precision range coder with BigInt. The algorithm maintains an interval [lo, hi) and narrows it with each encoded bit:

- Split the interval proportionally:

mid = lo + range × p₀ / total - Encoding a 0? →

hi = mid - Encoding a 1? →

lo = mid - When lo and hi agree on their leading bits, shift those out

A "pending bits" mechanism handles the annoying case where lo and hi straddle the midpoint — those bits wait in limbo until the next unambiguous output.

Why 48-bit instead of 32-bit? Precision. The range × p₀ / total calculation accumulates rounding error over long sequences. 48 bits keeps it honest.

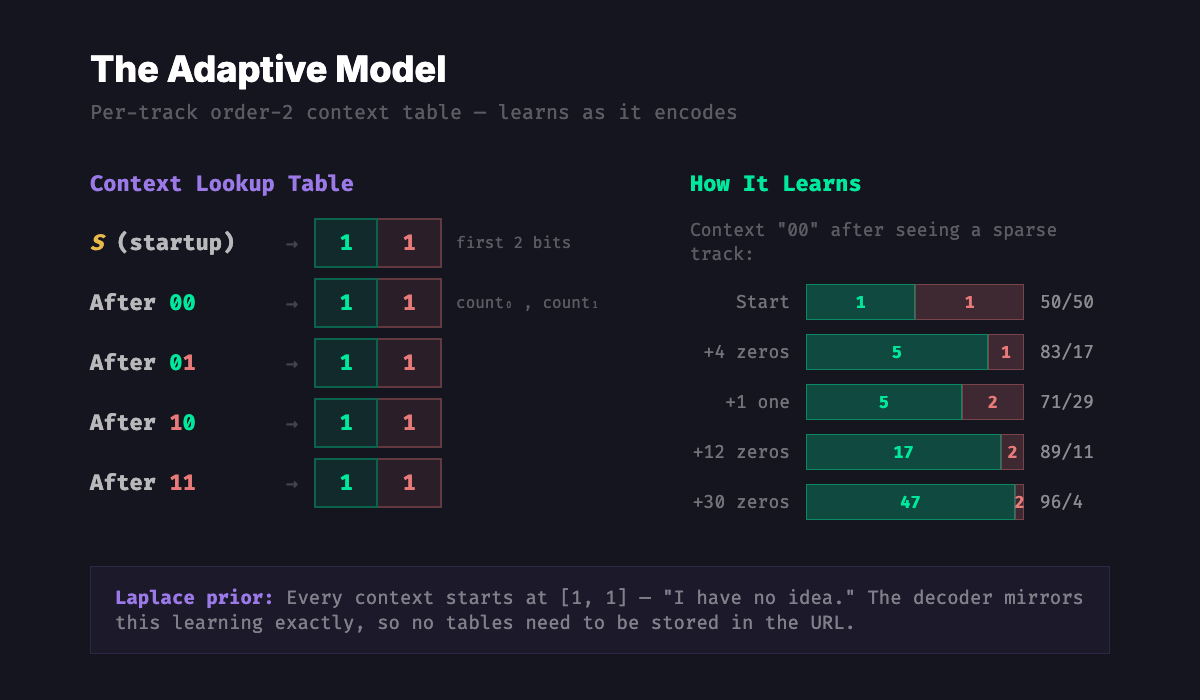

The Adaptive Model

Each track gets its own model — a tiny lookup table:

Every context starts at [1, 1] — the Laplace prior, or "I have no idea, maybe 50/50?" As bits flow through, the counts update and predictions sharpen. The decoder mirrors this exactly, so it stays perfectly in sync without needing any extra data in the URL.

URL Encoding

The binary payload gets base64url-encoded (RFC 4648 §5): standard base64 but with - instead of + and _ instead of /, padding stripped. Three bytes become four characters. Pure JS via btoa/atob — zero dependencies.

Old-format URLs (hex with dot separators) still work — the app detects them, decodes, re-encodes in the new format, and silently updates the URL bar. Your old bookmarks survive.

The Results

Real Beats, Real Numbers

| Beat | Raw bits | Bitpacked | Arithmetic | URL chars |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16-step pattern | 128 | 16 B | 13 B | 22 |

| 32-step trap | 256 | 32 B | ~12 B | ~22 |

| 64-step periodic | 512 | 64 B | 14 B | 24 |

| 236-step complex | 1,888 | 236 B | 119 B | 164 |

| 256-step random | 2,048 | 256 B | ~176 B | 240 |

| Empty 16-step | 128 | 16 B | 7 B | 14 |

| Empty 256-step | 2,048 | 256 B | ~7 B | 14 |

That empty 256-step grid compressing to the same 14 characters as the empty 16-step one? Entropy doing its thing — silence contains no information, regardless of how long you're silent for.

How Close to Perfect?

For a 16-step beat (17% density):

- Shannon floor: ~11 bytes

- My output: 13 bytes

- Gap: 2 bytes. One byte is the arithmetic coder's flush overhead (unavoidable). The other is the Laplace prior warming up on small data.

For a 236-step beat (19% density):

- Shannon floor: ~112 bytes

- My output: 119 bytes

- Gap: 7 bytes (~6% overhead)

I'm leaving pennies on the table, not dollars.

The Losers, Ranked

On the 16-step beat (128 bits of grid data):

| Method | Grid bytes | What went wrong |

|---|---|---|

| Arithmetic (mine) | 13 | Nothing. ~1 byte flush overhead. |

| Raw bitpack | 16 | No compression at all |

| Brotli (quality 11) | 23 | Framing overhead bigger than the data |

| Deflate (level 9) | 31 | Huffman tables alone weigh more than the grid |

| RLE | 66 | 2 bytes per run × many short runs = disaster |

General-purpose compressors need ~500–1,000 bytes of input before their overhead pays for itself. Below that, they're anti-compressors. My arithmetic coder has zero framing overhead — the only cost is that ~1 byte flush at the end.

Try It

Make a beat on BeatURL and watch the URL change as you toggle cells. The entire state lives in that URL — copy it, share it, bookmark it. No sign-up required.

The full source is on GitHub. The compression logic is all in the encoder module.

Want to Go Deeper?

- Shannon, "A Mathematical Theory of Communication" (1948) — the paper that started it all

- Arithmetic Coding for Data Compression — Wikipedia overview with worked examples

- Data Compression Explained — Matt Mahoney's guide to the fundamentals

- Introduction to Data Compression — CMU lecture notes on the math

- Range encoding — the practical variant I implement (bonus: no patent drama)