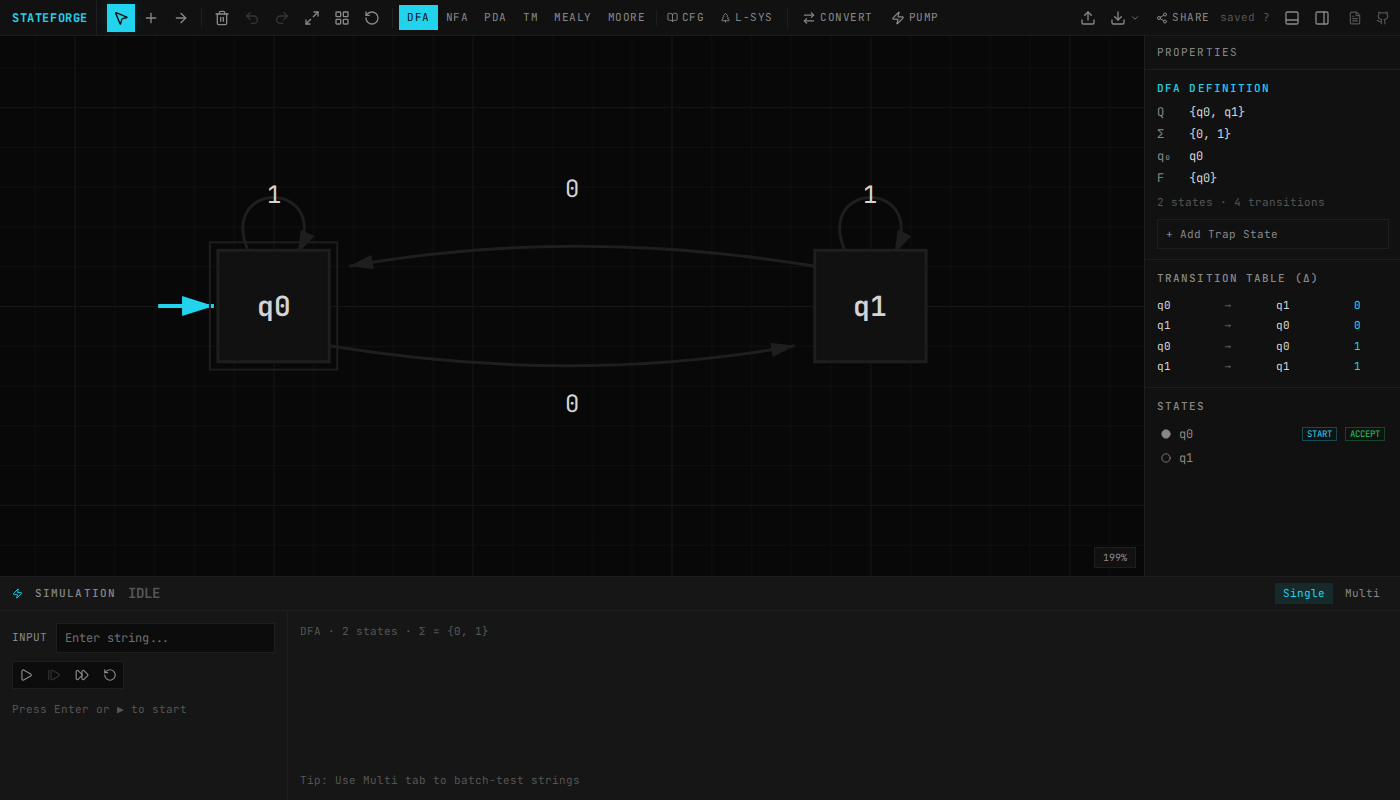

How I Rebuilt JFLAP for the Browser

Porting a 30-year-old Java automata simulator to a modern web app with URL sharing and step-through algorithm visualization.

In my third semester, our DSA professor walked in with his laptop connected to the projector, opened a .jar file, and spent twenty minutes building a DFA on screen. That was my introduction to JFLAP. A Java desktop app, built at Duke University, that's been the automata theory teaching tool for decades. We used it for every assignment that semester.

I was running Elementary OS at the time. JFLAP ran fine. For the final assignment we had to record a YouTube video solving a question and building the DFA in JFLAP. I promptly deleted that video after results came out. Not a YouTube star.

Try it live: stateforge.vercel.app · Source code: github.com/Royal-lobster/stateforge

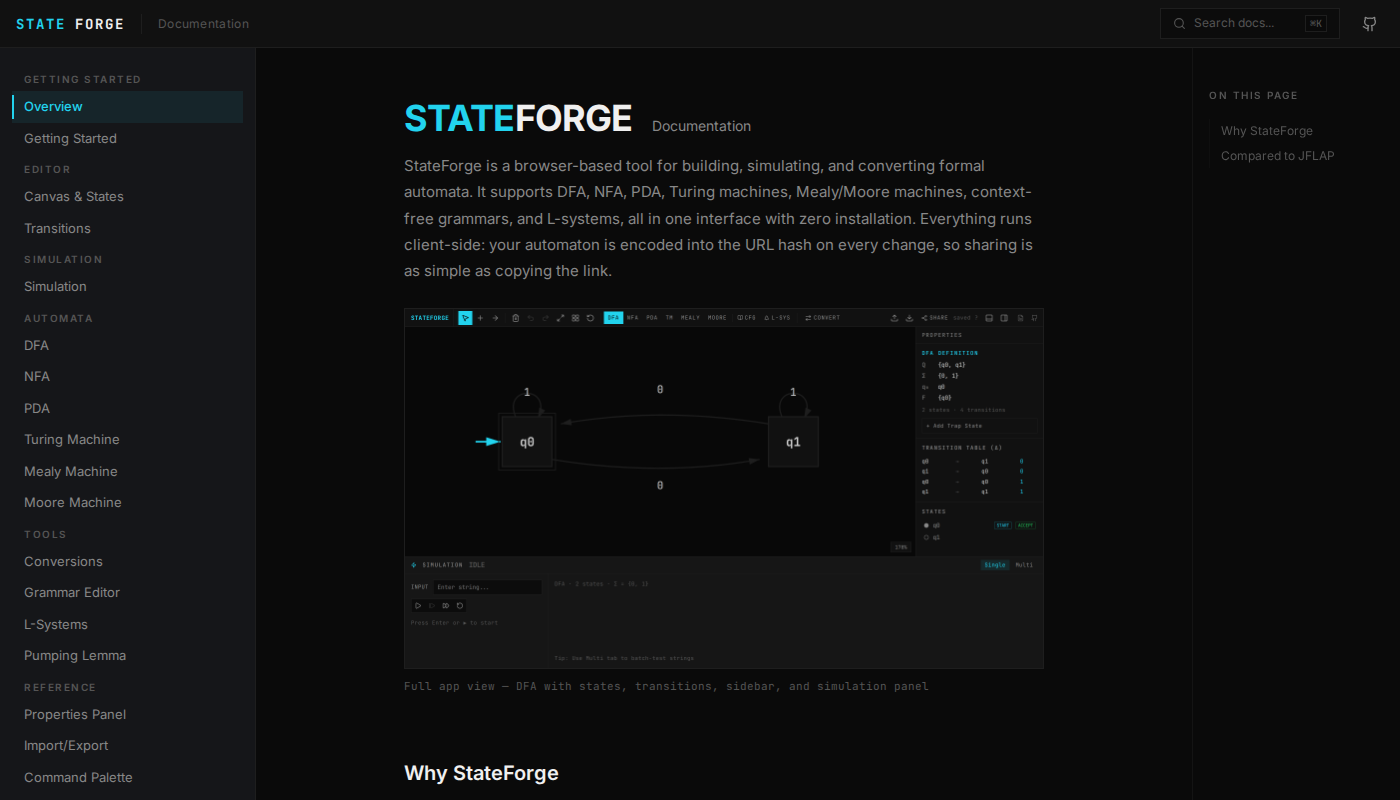

A few years later I started wondering what JFLAP would look like as a web page. URLs instead of screenshots. No .jar file. That turned into StateForge.

What JFLAP Gets Right

JFLAP is good software. Susan Rodger and her students at Duke have been working on it since 1990. You draw states, drag transitions, step through input strings, and watch the machine work. A 2011 review in ACM Inroads called it "the most sophisticated tool for simulating automata" with "effort unparalleled in the field" (Chakraborty et al., 2011).

It covers DFAs, NFAs, pushdown automata, Turing machines, grammars, regular expressions, and the conversions between them. An entire semester in one piece of software.

I didn't want to replace any of that. I wanted to change how it gets to students.

The Sharing Problem

JFLAP runs fine on every OS. It's Java. The problem is what happens after you build your automaton.

When I had to submit assignments, the workflow was: build the automaton in JFLAP, take a screenshot, paste it into a document. If the professor wanted to check my work, they'd need my .jff file, their own JFLAP install, and a few clicks to load it. In practice, everyone just looked at screenshots.

That final assignment, the YouTube video? That's the best option JFLAP gives you when you want someone to watch an automaton run step by step. There's no "click this link" alternative. You need the app installed, the file transferred, and someone on the other end who knows how to load it.

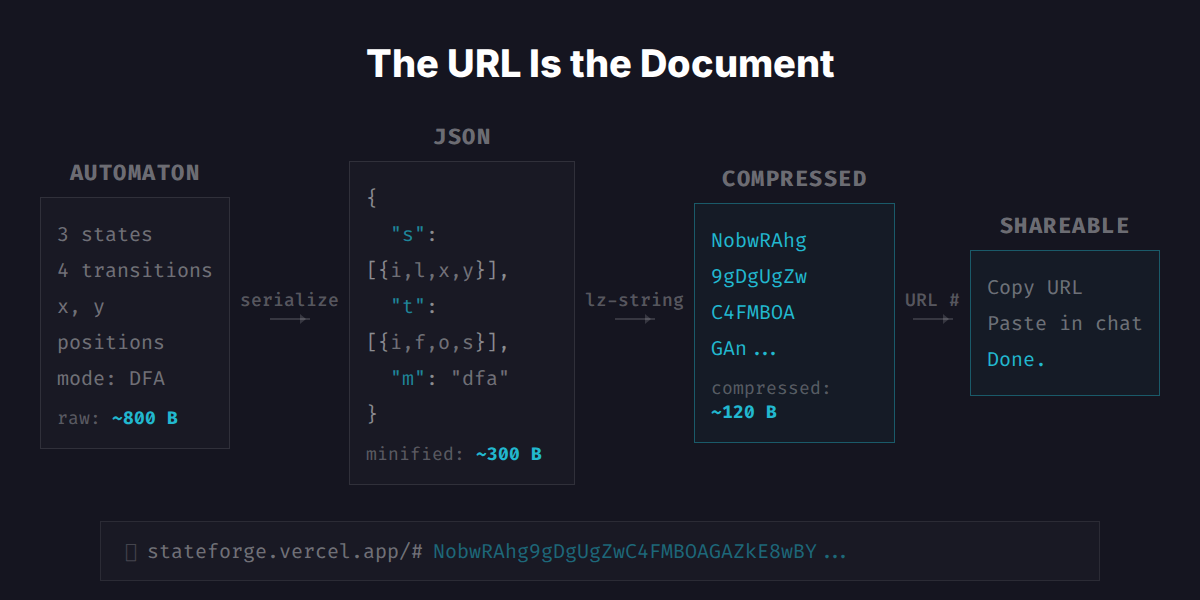

What if the entire automaton just lived in a URL?

The URL Is the Document

StateForge puts the automaton in the URL. Every state, transition, and position serializes into JSON, compresses with lz-string, and goes into the URL hash.

I use this pattern in most of my apps. But the challenge here is different from something like BeatURL, where the state is a flat grid of 2,048 binary cells. Automata are graphs with floating-point positions, string labels, and arbitrary connectivity. The serialization format has to be compact:

interface SerializedAutomaton {

s: Array<{ i: string; l: string; x: number; y: number;

n: boolean; a: boolean }>;

t: Array<{ i: string; f: string; o: string; s: string[] }>;

m: Mode; // "dfa" | "nfa" | "pda" | "tm" | ...

g?: string; // grammar text, when in CFG mode

}Short keys, rounded coordinates. A 3-state DFA compresses to about 120 bytes in the URL. A 10-state NFA with epsilon transitions lands around 400 bytes. Well within URL length limits.

One trick that kept things simple: PDA transitions encode their stack operations directly in the label string. A transition label like "a, Z → AZ" means "read 'a', pop 'Z', push 'AZ'." That string is both what the user sees on the canvas AND the serialized data in the URL. No separate PDA serialization path, no special cases. The label is the data.

// PDA transitions survive round-trip: push/pop info

// is encoded in symbols[] labels (e.g. "a, Z → AZ")

t: transitions.map(t => ({

i: t.id, f: t.from, o: t.to, s: t.symbols

})),So a student finishes their NFA-to-DFA conversion, copies the URL from the address bar, pastes it into Slack. The TA clicks it. The automaton loads in their browser, states and transitions and all. If you already have .jff files from JFLAP, StateForge reads those too via the file picker.

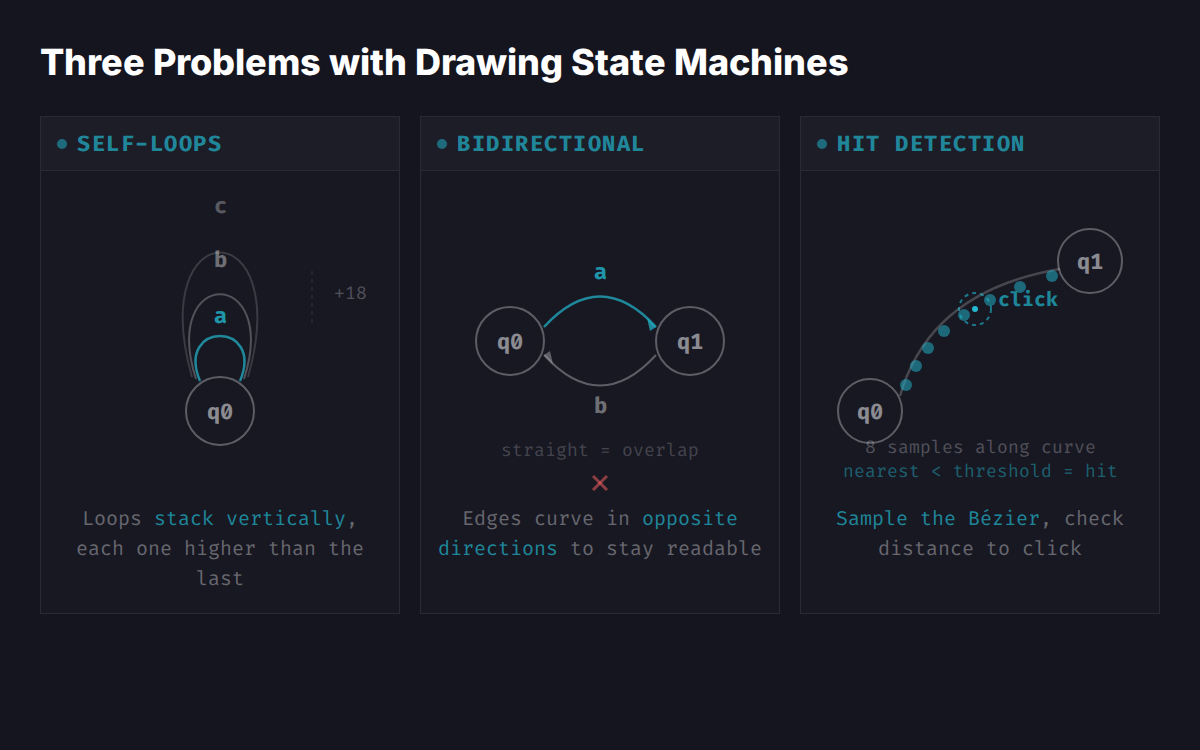

Drawing State Machines

Graph libraries like Cytoscape.js and D3-force handle layout, but they're opinionated about what a graph looks like. I needed self-loops that stack, bidirectional edges that curve apart, and transition labels that sit on arcs. Every library I tried either couldn't do self-loops well or fought me on custom rendering. So I wrote a custom renderer. About 750 lines.

Multiple self-loops on the same state stack vertically, each arc sitting 18 pixels higher than the previous one. Bidirectional edges (A→B and B→A) curve in opposite directions so they don't overlap. Click detection works by sampling 8 points along each Bézier curve and checking distance to the click position. Not mathematically perfect, but it runs on every mouse-move for hover effects, and 8 samples on a 200-pixel curve means you'd have to try hard to miss.

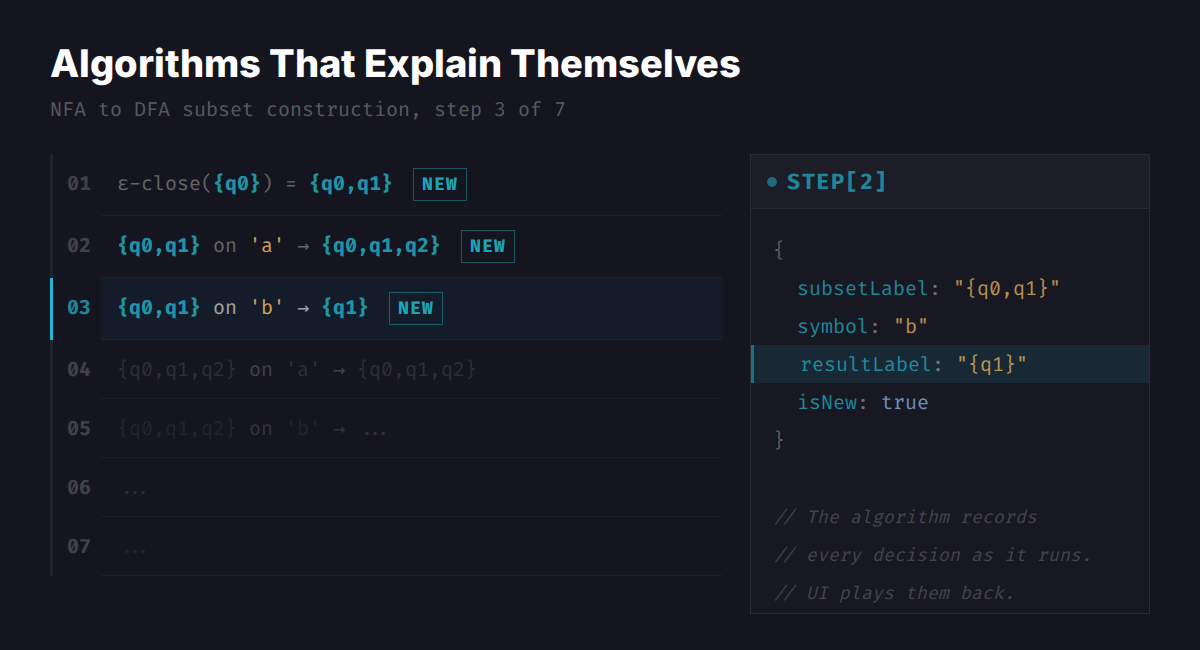

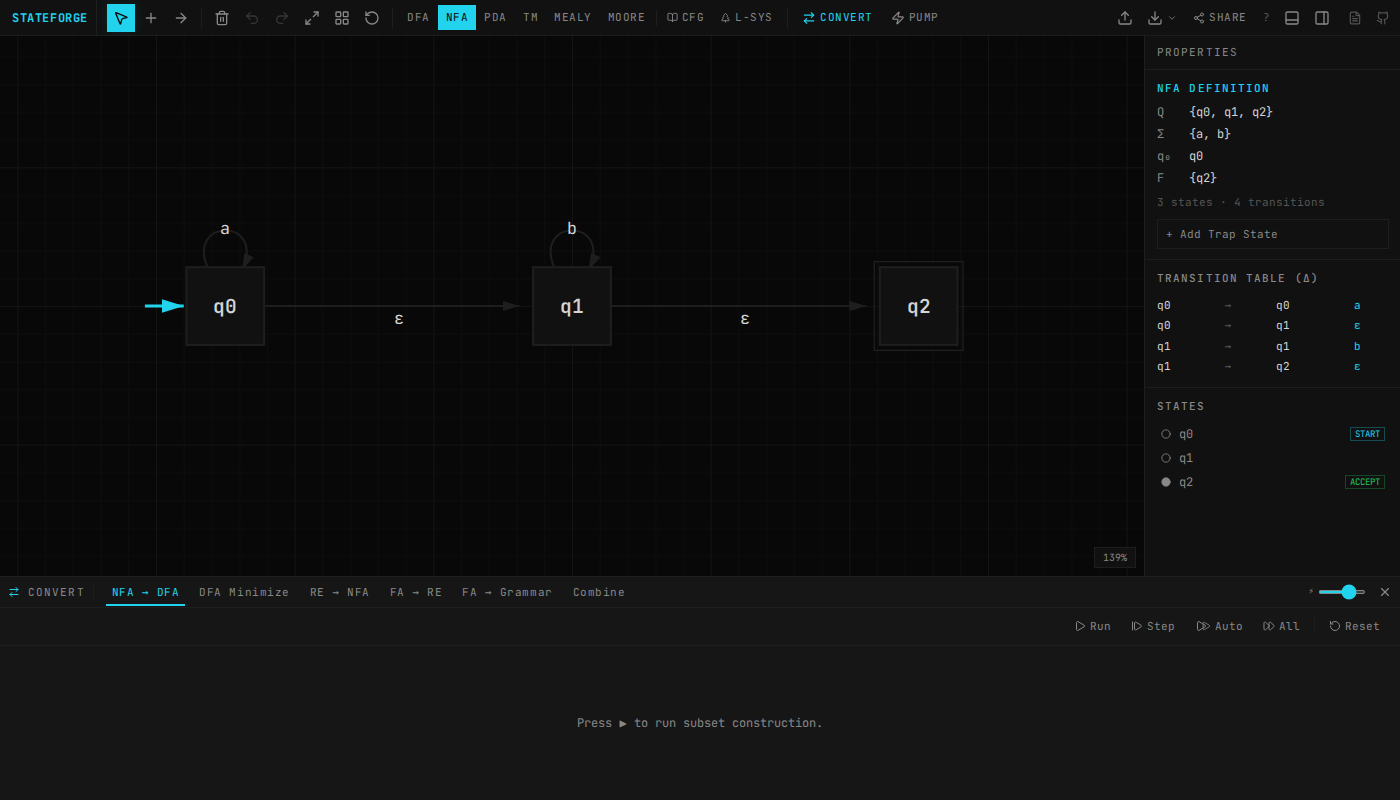

Algorithms That Explain Themselves

NFA-to-DFA subset construction, DFA minimization, Thompson's construction, state elimination. These algorithms are in every textbook. The algorithms themselves aren't the hard part. Making them step-through-able is.

Take subset construction. The algorithm is BFS: start with the ε-closure of the initial state, then for each unprocessed subset, compute what you reach on each input symbol. Maybe 80 lines. Straightforward.

But I wanted the UI to replay it step by step. "We're looking at subset {q0, q1}, consuming symbol 'a', and the result is {q0, q1, q2}, which we haven't seen before." That means the conversion function can't just return a DFA. It returns the DFA and a diary of every decision:

interface SubsetStep {

subsetLabel: string; // "{q0, q1}"

symbol: string; // "a"

resultLabel: string; // "{q0, q1, q2}"

isNew: boolean; // true — first time seeing this subset

}The UI plays diary entries back one at a time. You see the subset being examined, the symbol being consumed, the new subset appearing on the canvas. Click "next step" and the algorithm advances.

DFA minimization does the same thing. It records each pair of states marked as distinguishable, with the reason: "q1 and q3 are distinguishable because on input 'a', q1 goes to q2 and q3 goes to q4, which were already marked in round 1." Thompson's construction logs each fragment merge.

The bookkeeping code ends up longer than the algorithm. Subset construction is 80 lines of BFS plus 40 lines of step recording. The distinguishability logic in the table-filling algorithm is shorter than the code that formats the reason strings.

The upside is that the UI stays completely decoupled. It reads from an array and highlights things on the canvas. It doesn't know or care which algorithm produced the steps.

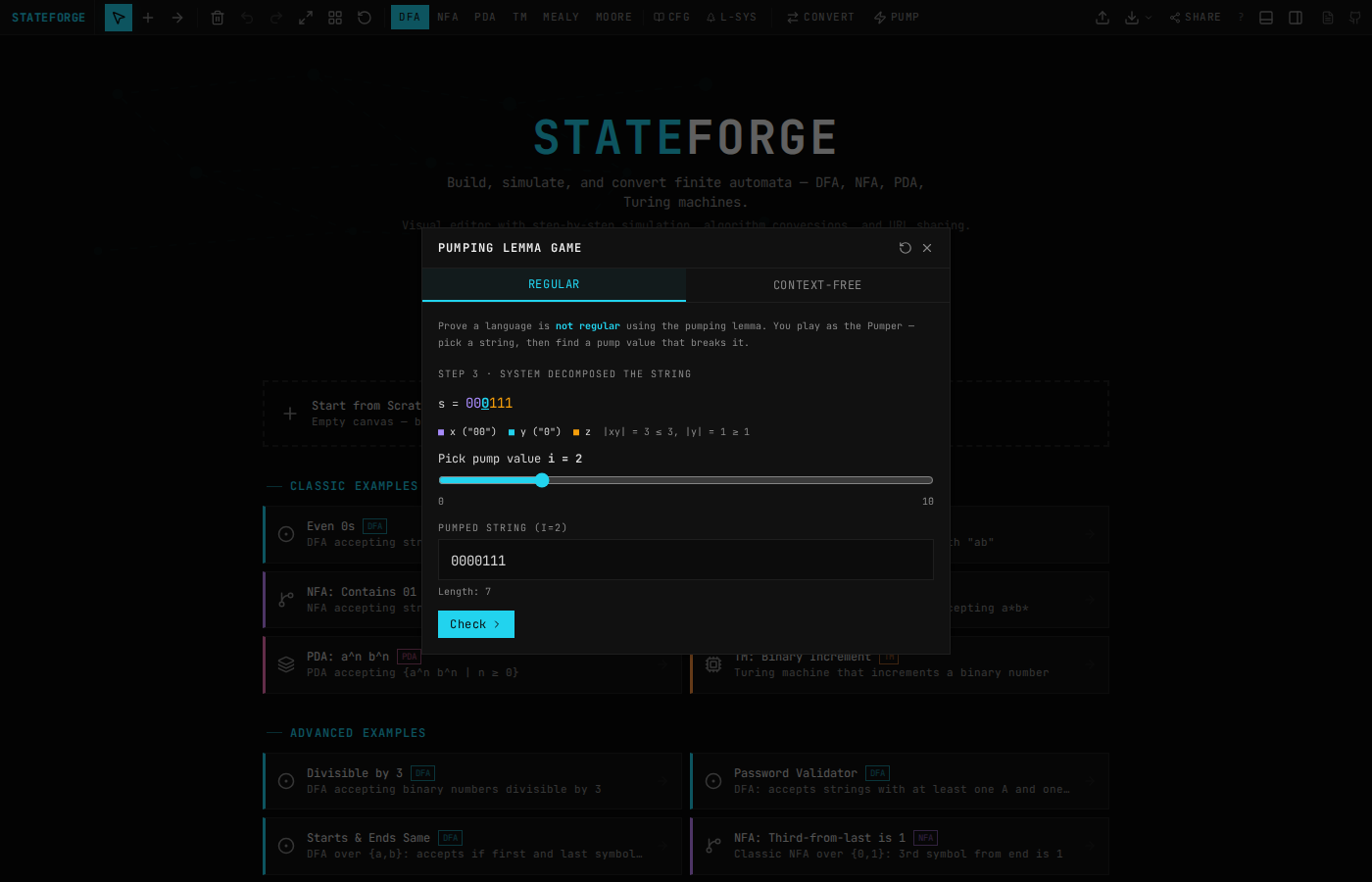

The Pumping Lemma as a Game

The pumping lemma is how you prove a language isn't regular. Students hate it. The proof structure is adversarial: for any pumping length p, you pick a string, then for any valid decomposition xyz, you need to find some pump count i where xy^iz falls outside the language.

That quantifier alternation (∀p, ∃s, ∀xyz, ∃i) maps naturally to a two-player game. The system plays the "for any" side. You play the "there exists" side.

StateForge turns this into an interactive sequence: the system picks p, you pick a string at least that long, the system shows all valid decompositions, you pick a pump value i. If every decomposition has some i that pumps the string out of the language, you've proved it's not regular. The same flow works for the context-free pumping lemma too, just with a five-part decomposition (uvxyz) instead of three.

Each built-in language provides a hint function that generates a good candidate string at the right length. For {a^n b^n | n ≥ 0}, the hint at pumping length p is a^p b^p. The student can ignore the hint and try their own string, but the hint gives them a starting point when they're stuck.

I never liked doing pumping lemma proofs on paper. You end up enumerating cases by hand and second-guessing whether you covered all decompositions. The prover handles the enumeration so you can focus on the argument.

Nondeterministic PDA Simulation

Most PDA simulators pick one execution path and call it done. If the path rejects, you don't know whether a different branch would have accepted. That's a problem for nondeterministic PDAs, where the whole point is that multiple paths exist.

StateForge runs all branches at once. Every configuration (current state + stack + input position) gets explored in parallel, BFS-style. Each configuration stores a parent pointer back to the configuration that spawned it:

interface PDAConfig {

stateId: string;

stack: string[];

inputPos: number;

id: number;

parentId: number | null; // for tree display

transitionUsed: string;

}The result is a configuration tree. You can see every branch the PDA explored, which ones accepted, which ones got stuck, and trace back from any accepting configuration to see the full path. A safety valve caps exploration at 10,000 configurations to keep the browser responsive.

![PDA simulation running on input "aabb", showing the active state highlighted, stack contents [AAZ], and simulation controls](/blog/jflap-for-the-browser/images/pda-simulation.png)

One subtle bit: stack operations in the PDA use the convention that the leftmost character of the push string goes on top. So push: "AZ" means push Z first, then A on top. The code reverses the push string before applying it: entry.push.split('').reverse(). Small detail, easy to get wrong, causes confusing bugs if you don't match the textbook convention.

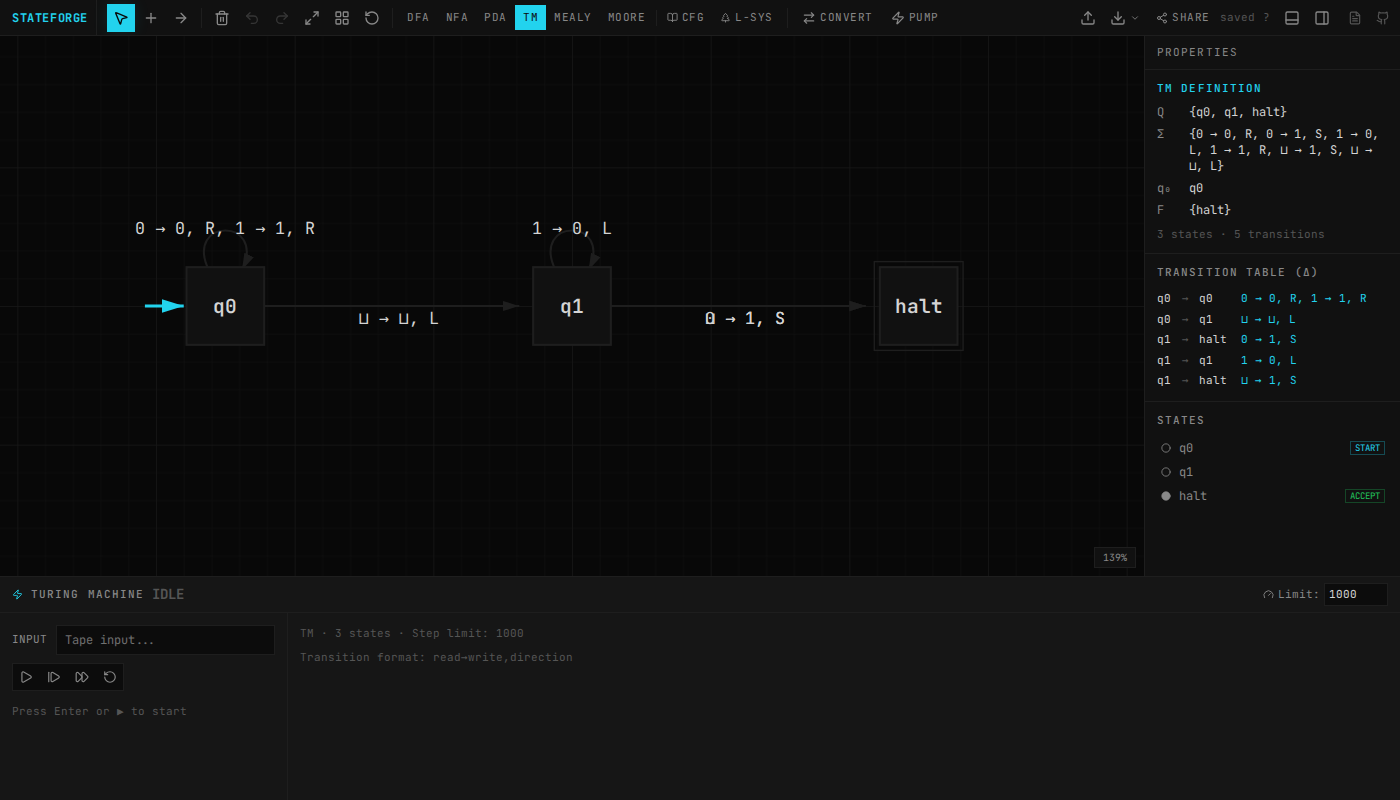

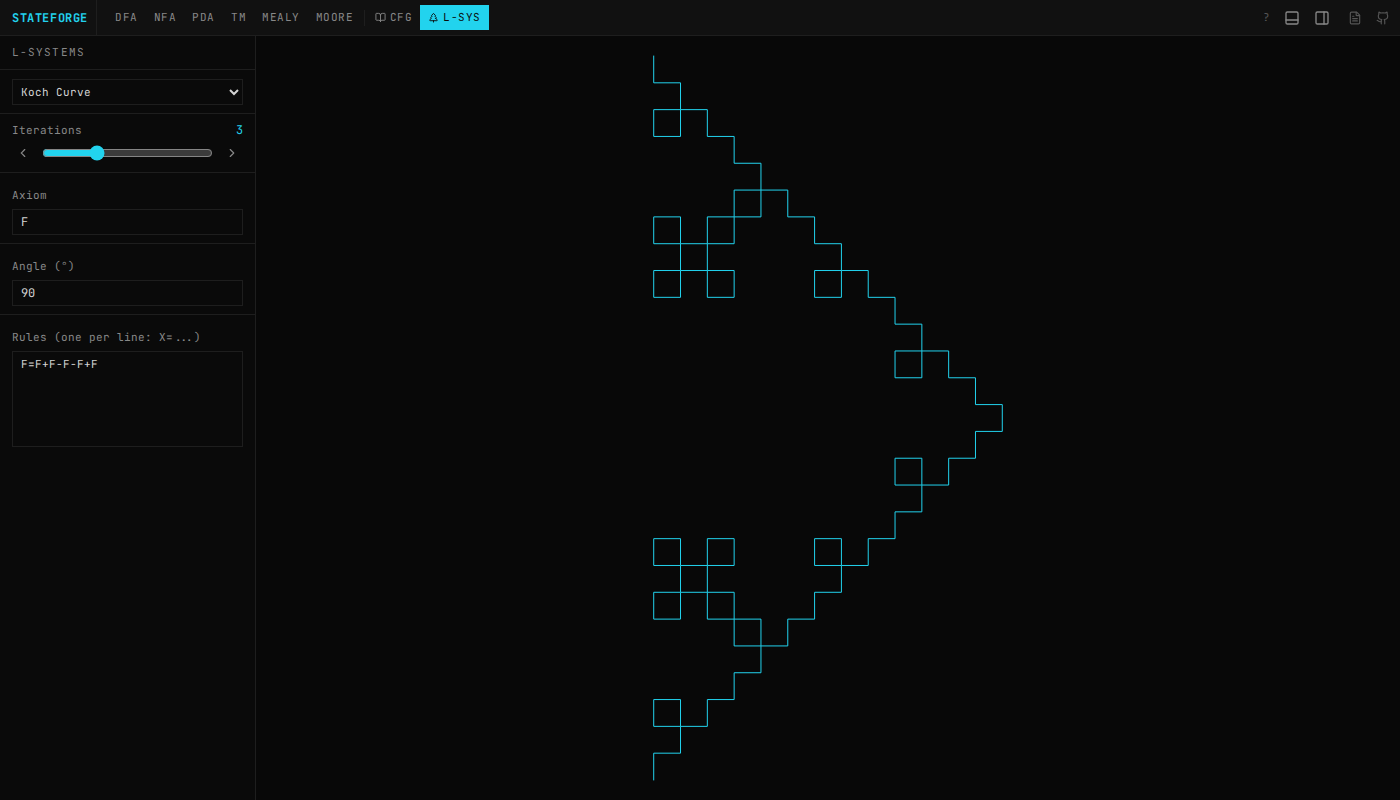

StateForge also covers Turing machines with tape visualization, Mealy/Moore transducers, regex-to-automata conversion (and back), grammar transforms (CNF, GNF), CYK parsing, and L-systems with turtle graphics. Everything has a docs page walking through how it works.

~3,000 lines of algorithm code across five TypeScript files, no external dependencies.

Try It

Open stateforge.vercel.app and draw something. Convert an NFA to a DFA, watch subset construction fill in the table, then copy the URL and send it to someone. That's the whole point.

The source is on GitHub. The interesting files are src/lib/conversions.ts (NFA/DFA conversion, minimization, regex) and src/lib/grammar.ts (grammar parsing and transforms).

References

- JFLAP — the original, by Susan Rodger and students at Duke University. 30+ years of development. If your professor requires JFLAP, use JFLAP.

- Chakraborty, Saxena, Katti, "Fifty years of automata simulation: a review" (2011) — the ACM Inroads review that called JFLAP's development "unparalleled"

- Sipser, Introduction to the Theory of Computation — the textbook that defines how most of these algorithms are taught

- Thompson, "Regular Expression Search Algorithm" (1968) — the construction that converts regex to NFA